Implications for Defendants and their Insurers – Lloyd v Google

November 2021

Background

In Lloyd v Google LLC [2021] UKSC 50, Mr Lloyd, former ‘Which’ magazine editor and FCA board member, claimed Google breached the Data Protection Act 1998 (“the DPA 1998”) through Google’s collection and sale of browser generated information from 4.4million iPhone users without their consent. Mr Lloyd sought to bring a class action against Google on behalf of all 4.4million affected individuals.

There are two types of class action available to claimants for such mass data breach claims:

- Opt-out “representative actions” under CPR 19.6; and

- Opt-in Group Litigation Orders (“GLOs”) under CPR 19.10.

Mr Lloyd sought to pursue his claim against Google as a representative action. Claimant firms and litigation funders prefer such representative actions because they are “opt-out” class actions where all persons falling in the represented class form part of the litigation (in this case, 4.4million iPhone users), unless they take proactive steps to opt-out. In contrast, GLOs are “opt-in” and have traditionally suffered low take-up rates of eligible claimants opting in, making them less attractive to claimant lawyers and their funders.

The DPA 1998 and its successor, the GDPR, provide affected individuals statutory claims for compensation for personal data breaches where they suffer material loss (i.e. financial losses or personal injury) and distress.

However, opt-out representative actions have a narrow “same interest” requirement for all represented claimants. If there are differences between claimants requiring individual assessment of their claims and losses, opt-out representative actions are not permitted. It is inherent that any material losses and distress suffered may differ between affected individuals in mass personal data breaches. For example, my leaked bank account details may lead to me losing £1,000 but you may lose nothing. Your distress at the loss of your health records may be worse than my distress for the loss of mine. This makes claims for such losses unsuitable for opt-out representative actions.

To try and get around this, Mr Lloyd did not seek compensation for any financial losses or distress suffered by any of the 4.4million individuals. Rather, he claimed that a uniform sum of compensation should be awarded to each data subject based on the infringement of the individuals’ data protection rights and consequent “loss of control” of the individuals’ personal data. Mr Lloyd argued such “loss of control” was the lowest common denominator of “damage” that was common to all of the 4.4million individuals and therefore satisfied the “same interest” requirement.

Mr Lloyd alternatively claimed that the individuals affected were entitled to “user damages”. “User damages” are quantified by the hypothetical fee that would have been agreed to permit use of the individual’s property. Mr Lloyd argued that Google should pay a uniform sum to each member of the class calculated by the amount they could have reasonably charged for releasing Google from the duties it breached.

Because Google is a Delaware corporation, Mr Lloyd needed the court’s permission to serve outside the jurisdiction. The application was contested by Google on the grounds that the claim had no real prospect of success.

In 2018, the High Court refused permission for Mr Lloyd to serve Google out of the jurisdiction. However, in 2019, the Court of Appeal overturned this decision. On appeal to the Supreme Court, the key issues in dispute were:

- Whether compensation can be awarded under the DPA 1998 for “loss of control” of data alone without proof that it caused material damage or distress as a result of the data breach.

- Whether the individuals satisfied the “same interest” test so that the claim is suitable to proceed as an opt-out representative action.

The Supreme Court’s Decision

The Supreme Court ruled in favour of Google and found:

- “Loss of control” or “user damages” are not recoverable under the DPA 1998. The Supreme Court held, to recover compensation under the DPA 1998 there must be some “damage” suffered by the data subject as a result of the breach and this means material damage (such as financial loss) or distress which is distinct from and caused by the breach. “Damage” under the DPA 1998 did not extend to “loss of control” of personal data or “user damages”;

- Even if compensation for “loss of control” or “user damages” were recoverable, a representative action could not proceed as the 4.4million individuals did not satisfy the “same interest” test. There were differences between affected individuals in the amount and type of personal data acquired and used by Google without consent, and there would be differences in the affected individuals’ attitudes to such acquisition and use, meaning different awards of compensation to individuals. Therefore, the claim was not viable as a representative action.

Implications for defendants and their Insurers

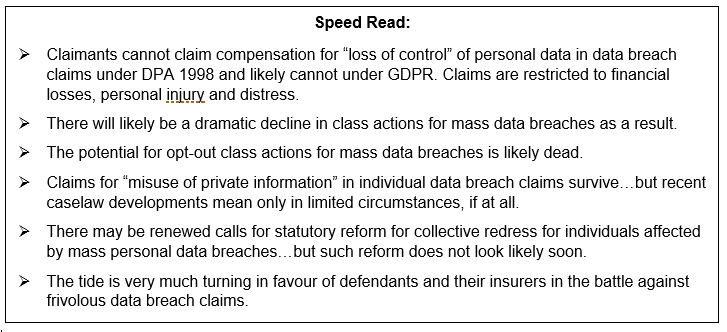

The absolute death of “loss of control” claims under DPA 1998

The categoric effect of Lloyd v Google is that Claimants are unable to pursue data breach actions for compensation under the DPA 1998 for “loss of control” of their personal data. Claimants have routinely added such head of claim to their data breach actions since the Lloyd Court of Appeal judgment. It is clear now, though, that statutory compensation claims under the DPA 1998 are limited to compensation for financial losses, personal injury or distress caused by the personal data breach.

The likely death of “loss of control” claims under UK GDPR

The Supreme Court made clear that they only considered the DPA 1998 in reaching their conclusion. This has led many to query whether actions for breach of data could be successfully brought under the present UK GDPR regime (as implemented in the UK by the Data Protection Act 2018).

The writer’s view is that “loss of control” damages would not be recoverable under the UK GDPR, either.

There is reference to individuals potentially suffering “loss of control” of their personal data in a recital to the GDPR (albeit in a different context to compensation). However, there are two reasons why a claim for “loss of control” under the GDPR will still likely fail.

Firstly, a key reason for the Supreme Court’s findings that “loss of control” damages were not recoverable under the DPA 1998 was the language of the Act. Section 13 DPA 1998 gives individuals the right to claim compensation for material damage or distress suffered “by reason of” a breach of the DPA 1998. The equivalent provision under the GDPR is article 82(1) which provides a right to compensation to a person who has suffered material or non-material damage “as a result of an infringement of” the GDPR. The language of article 82(1) GDPR is therefore worded in similar terms to section 13 DPA 1998 in that it distinguishes between the damage and the infringement, with the former having to occur by reason of the latter. Mere breach without recoverable damage is not enough. Neither provisions refer to “loss of control”.

Secondly, Mr Lloyd was initially successful in the Court of Appeal due to the Court accepting the application by analogy of the decision in Gulati v MGN Ltd [2017] QB 149, a celebrity phone hacking case. In Gulati, the Court awarded compensation for mere “loss of control” of private information under the cause of action of “misuse of private information” (“MPI”). The Court of Appeal decided that statutory compensation claims under the DPA 1998 for personal data breaches and claims for MPI shared the common source of protection of the right to privacy under the European Convention on Human Rights. Therefore, the claim for compensation for “loss of control” of personal data could apply by analogy. However, the Supreme Court rejected this argument outright, both on the proper interpretation of section 13 DPA 1998 and the flawed logic of the argument by analogy. The reasons for the Supreme Court’s rejection of this argument for the DPA 1998 would equally seem to apply to the GDPR.

Therefore, had this claim been brought under breach of GDPR, it is difficult to see how the Supreme Court would have reached a different conclusion.

The likely death of opt-out class actions for data breach claims

This is the big one. Had Mr Lloyd’s claim been successful, it would have provided ravenous claimant lawyers and litigation funders with the perfect recipe for data breach class actions: every time there is a large personal data breach, pursue an opt-out representative actions for “loss of control” damages alone (ignoring any financial loss or distress suffered) for all affected individuals, with no need to look at the claims individually. Whilst the claims may be small individually (Lloyd claimed £750 each), the total compensation could be huge for large personal data breaches (c.£3billion in Google’s case for the 4.4million affected individuals).

Without a change in the law, the Supreme Court’s decision is probably the death knell for opt-out class actions for mass data breaches. It is difficult to imagine other claims where there will not similarly be differences between affected individuals to satisfy the “same interest” test for opt-out representative actions.

Claims under the DPA 1998 and GDPR for financial losses, personal injury and distress would almost certainly be different between affected individuals – recognised by the omission of these claims in Lloyd.

Similarly, claimants often add overlapping claims for MPI (misuse of private information) (see further below) and/or “breach of confidence” to DPA 1998/GDPR statutory claims in data breach actions. Whilst compensation for “loss of control” without financial losses or distress are potentially available in MPI claims following Gulati, such claims require proof of an expectation of privacy over the personal data breached. As noted in Lloyd, this would seemingly require evidence from each individual of such expectations and therefore make them unsuitable for representative actions. MPI and breach of confidence claims were also omitted in Lloyd, no doubt in recognition of the difficulties in establishing a “same interest” between all affected individuals.

A dramatic decline of class actions for data breach claims

So, how might claimants now bring class action claims for mass personal data breaches?

There are likely two main routes. Firstly, “opt-in” GLOs (Group Litigation Orders). There is some precedent: an opt-in GLO class action was brought against British Airways and settled in July 2021, following a mass personal data breach affecting 430,000 customers (see our article here).

However, as mentioned above, there are historically low opt-in rates for data breach GLOs. Out of 430,000 affected individuals in British Airways, it is estimated only just over 22,000 (about 5%) opted into the GLO. In another previous GLO case against Morrisons following a personal data breach affecting nearly 100,000 Morrisons employees, only 9% of the affected employees joined the action. A lot of initial cost is incurred by claimants (or more appropriately the litigation funder) in building the class. Low take-up levels can make class actions claims economically unviable.

The second potential route is what the Supreme Court called a two-stage “bifurcated” process. The first stage would be brought as an opt-out representative action to decide the common issues of law or fact (e.g. a declaration of breach of the DPA 1998/GDPR to establish liability), leaving the second stage to proceed as a opt-in claim for individualised assessment of losses. The Supreme Court stated, in theory, Lloyd could have been brought as such as a bifurcated process.

However, as noted by the Supreme Court, this two-stage process is unlikely to be an attractive proposition for litigation funders. The first stage would not generate a return but carry a risk of an adverse costs order if liability was not established. The second stage would still carry the risk of the historic low opt-in rate of potential claimants.

Such bifurcated claims may be an attractive route for privacy activists and campaigners instead, some of whom have significant financial benefactors.

It therefore remains to be seen what appetite remains now for data breach class actions via opt-in GLOs or bifurcated processes. There can be no doubt, though, that such appetite will be much less compared to the position had opt-out representative actions for “loss of control” been given the green light.

Misuse of private information claims for individual data breaches may increase – though only for certain types of claim

It is now routine for claimants to include claims for MPI in data breach actions along with statutory claims for compensation under the DPA 1998/GDPR. The tort of MPI protects information which is established to be private in nature.

As mentioned above, Mr Lloyd’s idea for loss of control damages in fact came from Gulati, which was an MPI claim. In Gulati, the court found that the intrusion of privacy (in being hacked), separate to any kind of distress, was itself something which justified an award of damages for loss of control of such private information.

Although obiter, the Supreme Court in Lloyd made clear that it had no problem with the propositions in Gulati. The Supreme Court stated that MPI is a tort involving strict liability for deliberate acts. As such, damages may be awarded without proof of material damage or distress. In addition, the Supreme Court made clear that “user damages” may be a form of compensation in MPI cases.

Claimant lawyers and funders like pleading MPI claims for data breaches because they then may amount to “privacy proceedings” for which ATE premia can be recovered from defendants (improving their profitability and increasing the exposure for defendants and their insurers). Whilst the judgment in Lloyd means claims for MPI will unlikely be viable for class actions, the Supreme Court’s clarification of the law in respect of the above will likely encourage more MPI to be made in individual actions.

However, defendants and insurers will be relieved that there are some particular difficulties with MPI claims for data breach actions and some recent helpful caselaw that has limited the types of case when such claims can be brought:

- As the Supreme Court noted in Lloyd, the claimant must establish that they had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the personal data breached. Not all personal data is private.

- In the recent case of Warren v DSG Retail Ltd[2021] EWHC 2168 (QB), the High Court found that there needs to have been a positive act by the defendant for MPI (and breach of confidence) claims. “Want of care” negligence by the defendant, such as failing to put in place sufficient security to protect against a hacker who obtained the personal data, is not enough.

- Similarly, the Supreme Court in WM Morrison Supermarkets plc v Various Claimants [2020] UKSC 12 found Morrisons were not liable for MPI (or breach of confidence) where a disgruntled employee deliberately and criminally breached the personal data of other employees by stealing and publishing it. The Supreme Court found, in such circumstances, it is the rogue employee who misused the private information (or breached the confidence) and not the defendant employer, and the defendant employer is not vicariously liable for the rogue employee acting in such way outside the scope of their employment.

- Finally, in the case just this month of Johnson v Eastlight Community Homes Ltd [2021] EWHC 3069, the High Court struck out the MPI and breach of confidence claims, leaving only the statutory claim for compensation under GDPR for the admitted data breach to proceed, on the basis they added nothing to the GDPR claim and would likely take up disproportionate and unreasonable court time and costs having regard to the small sums at stake.

Therefore, at first glance, Lloyd v Google is potentially helpful authority for claimants (and their litigation funders) for advancing MPI claims of loss of control and user damages in data breach actions. However, the effects of Warren and Morrisons may restrict such MPI claims only to cases where the claimant can point to some positive act by the defendant carried out by one of the defendant’s employees as part of their employment – such as accidentally emailing personal data to the wrong person – and not personal data breaches as a result of hacks and rogue employees. Depending upon how it is followed, Johnson may even prohibit MPI claims in all circumstances for low value data breach claims.

Statutory reform?

Following the Supreme Court’s likely fatal blow to opt-in representative actions for mass data breaches, and the problems with the remaining GLO and bifurcated class action routes discussed above, there may now be renewed calls for statutory reform to introduce a better collective method for redress for victims of mass personal data breaches.

Indeed, the Supreme Court specifically said “a detailed legislative framework would be preferable” and raised the benefits of collective claims: (1) avoiding unnecessary duplication in fact-finding and legal analysis; (2) making economical the prosecution of claims that would otherwise be too costly to prosecute individually; and (3) serving efficiency and justice by ensuring that actual and potential wrongdoers who cause widespread but individually minimal harm take into account the full costs of their conduct.

Earlier this year, following consultation (“UK Government response to Call for Views and Evidence – Review of Representative Action Provisions, Section 189 Data Protection Act 2018”) the Government concluded that there “is not a strong enough case for introducing new legislation” for non-profit organisations to bring collective actions on behalf of individuals. However, part of their decision in this respect relied upon the ongoing case of Lloyd v Google which they stated could lead to a successful form of collective action under current legislation. That has not obviously come to pass.

But what are the potential routes for providing such collective redress and how likely are they?

In 2009, the UK Government rejected a recommendation from the Civil Justice Council to introduce a generic class action regime applicable to all types of claim, preferring a “sector based approach”. So far, the Government has only brought in a collective redress scheme for competition law claims. This scheme allows opt-out class actions without the need for individual assessment of the claimants’ losses – i.e. the bar to representative actions for data breaches following Lloyd. Replicating the collective redress scheme for breaches of competition law for breaches of data protection law is therefore one possible avenue. There has been no sign from the Government about doing so to date, however.

In Europe, the EU Collective Redress Scheme is in the course of coming into force which includes collective actions for personal data breaches. However, following Brexit, the UK does not need to implement the Scheme and has shown no sign it will do so. Further, the Scheme has limitations: it will only empower consumer bodies to bring representative actions and only allows limited litigation funding.

Another potential reform for providing collective redress is the extension of the jurisdiction of the Information Commissioner. Whilst the Information Commission can investigate and fine companies for breaches of the DPA 1998/GDPR, the Information Commissioner cannot award compensation to affected individuals (whether individually or collectively) for personal data breaches – unlike, say, the Financial Ombudsman who can award compensation in the financial sector. The Government’s recent “Data: a new direction” consultation on reforms to the UK’s data protection regime did not include any proposals for granting the Information Commission such power. To the contrary, the consultation suggested more data controller-friendly reforms in the future.

The outlook for reform to provide collective redress for mass data breaches is therefore not a positive one, at least in the short term.

Conclusion

It is clear that Lloyd v Google is a positive result for defendants and their insurers defending data breach claims. We consider that the effect of Lloyd v Google is that the forecast has changed in relation to all class action claims for data breaches, primarily because they are unlikely to be an attractive proposition for litigation funders going forward.

Whilst we will likely see a dramatic decline in class actions, often frivolous individual claims for data breaches are still being received, which are often costly and disproportionate to defend. There is hope that the other recent helpful developments in caselaw in this regard will continue.

Download PDF