Designed to Succeed? – a focus on Contractors’ liability for design’

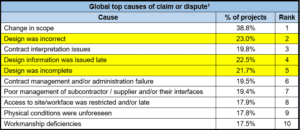

August 2024According to HKA’s Sixth Annual CRUX Insight Report ‘Forewarned is Forearmed’, which analysed the underlying causes of disputes on 1,801 projects across 106 countries with a cumulative capital expenditure value of over $2.2 trillion, design matters occupied 3 of the top 5 ranked causes of disputes globally:

If you are a contractor or sub-contractor with design responsibility, ensuring that contracts both up and down your supply chain contain appropriate and insurable design obligations is therefore of tremendous importance.

Insurance cover: why design obligations matter?

Contractors / sub-contractors with design responsibility will invariably be obliged to procure professional indemnity insurance cover in respect of their design and specification contractual obligations.

Generally speaking, most professional indemnity insurance (“PII”) policies will respond to and provide cover for claims where the insured has breached the common law standard of performing professional services with “reasonable skill and care [and diligence]” (or similar). In other words, PII policies provide cover against the insured being negligent in the performance of its professional duties and/or services.

However, PII policies usually exclude coverage for claims relating to alleged breaches of obligations that go beyond the common law standard of care (e.g. strict obligations) and for fitness-for-purpose (“FFP”) obligations. For example:

“Insurers shall not be liable to indemnify the Insured in respect of: Any Claim emanating from any performance warranty, guarantee, penalty clause or liquidated damages agreement unless the liability of the Insured would have existed in the absence of such warranty, guarantee, penalty clause or similar provision.”

For consistency with PII, strict obligations and FFP obligations in respect of design should be avoided to the extent possible!

Design obligations: the NEC4 ECC and JCT D&B 2024

NEC4 ECC Option X15

Option X15 of the NEC4 ECC provides drafting dealing with the contractor’s design.

Clause X15.1 states that the contractor “is not liable for a Defect which arose from its design unless it failed to carry out that design using the skill and care normally used by professional designing works similar to the works.” This is a very helpful starting point.

Caution should be taken when relying on Option X15 in isolation, however. As this is an optional clause and is not drafted so as to be an express overriding duty of care, there is a risk of parallel obligations arising. It would therefore seem that Option X15 on its own is not sufficient in addressing both strict obligations and FFP obligation in respect of design.

Of course, for those NEC4 ECC contracts whereby Option X15 is not selected to apply, the starting point should of course be to agree the incorporation of Option X15 (or an equivalent Z Clause) with the appropriate amendments to address the above.

JCT D&B 2024 Clause 2.17

Like the NEC4 ECC, the JCT D&B provides that the contractor is required to exercise reasonable skill and care in carrying out the design. Under the new JCT D&B 2024, this is drafted largely in an overriding manner (clause 2.17.1). However, it is important to note that the overriding duty wording is caveated “to the extent permitted by the Statutory Requirements…” and therefore this drafting does not operate as a complete ‘release’ for contractors. The effectiveness of this wording in protecting the contractor’s position will also largely depend on any amendments that are introduced (for example through a Schedule of Amendments, as we frequently see) to the definition of Statutory Requirements or core contractual provisions.

In relation to FFP, positively, the 2024 edition of the JCT D&B includes a new clarification at clause 2.17, which provides that under no circumstances will the contractor be subject to any duty, obligation, or liability which requires the contractor’s design to be FFP. This is a helpful addition.

However, the FFP exclusion (and suggested limit of liability clause in the corresponding guidance note) has not been drafted in an overriding manner, meaning that the risk of parallel obligations remains and so the contractor should still proceed with caution. For more information on the JCT D&B 2024, please see our earlier webinars, linked here and here (you will need to register for access to the recordings).

The risk: strict obligations (including parallel obligations) that cover design duties

If your contract or appointment contains strict or FFP obligations in respect of your design and specification duties, there is a significant risk that PII cover will, in respect of strict obligations, provide cover only to the extent the contractor was exercising reasonable skill and care, and provide no cover in respect of FFP. This exposes your business to the prospect of uninsured losses.

For contractors and sub-contractors who are given design responsibility, the dividing line between ‘design and specification’ duties on the one hand, and ‘works’ duties on the other, will often be blurred and/or difficult to clearly draw.

This poses a challenge because ‘works’ duties (which PII policies will not in any event cover) are understandably expressed as strict obligations where the contractor is expected to warrant a particular outcome or achieve specific criteria. However, there is a need (so PII cover will respond) to ensure that any ‘design and specification’ duties are not subject to those same strict or FFP obligations to which the ‘works’ duties are.

Strict or FFP obligations that directly or indirectly apply to ‘design and specification’ duties may not always be easy to spot. For example:

- Provisions to: (i) “ensure compliance with / adherence to” employer obligations in auxiliary documents (like Third Party or Project Agreements); or (ii) not to put the contractor in breach of the main contract are often expressed strictly, notwithstanding that these documents and/or main contracts contain requirements that relate to design and specification.

- Design and specification duties are often hidden in the contract documents in relation to which the contract may require strict compliance – for example, the NEC4 Engineering and Construction Contract at clause 20.1 states: “The Contractor Provides the Works in accordance with the Scope.”

- Even where the design provisions in standard form contracts are engaged (e.g. clause 2.17 in the JCT Design and Build Contract 2016 and Secondary Option X15 in the NEC4 Engineering and Construction Contract), amendments to these clauses (and/or the defined terms they utilise) are very frequently made and so undermine the protection they could afford a contractor.

Even if there is a clause in the contract which states design shall be exercised using “reasonable skill and care” (or similar), there may therefore be parallel obligations in the contract which nevertheless apply strictly or onerously and cover design duties which, if breached and are the subject of a claim, may fall uninsured.

Lessons from case law: food for thought!

There is a raft of case law that supports the importance addressing both strict obligations and FFP obligations, whilst ensuring that conflicting standards are not included in the various contract documents on a project.

Most will be familiar with the case of MT Højgaard A/S v E.ON Climate and Renewables UK Robin Rigg East Ltd [2017] UKSC 59. Amongst other things, this case demonstrates that parties, when conflicting/different standards are included in contract documents, will be required to meet the more rigorous of the different standards in the contract. This is a helpful reminder of the need to carefully review all contract documents at the outset of a project and prior to execution of the contract.

The principles established in the case of Højgaard v E.ON have subsequently been applied and tested in a number of cases.

Of note is the case of LDC (Portfolio One) Ltd v George Downing Construction Ltd [2022] EWHC 3356 (TCC). In this case, the contract included a requirement for the sub-contractor to complete the works in a manner that meant the Contractor was not in breach of the Main Contract. In addition, a separate duty of care clause was included. The Judge in this case held that clause 5.3.1 of the sub-contract, which imposed an obligation on the sub-contractor to exercise reasonable care, could not be relied on to supersede the obligation to ensure that the contractor was not placed in breach of its obligations under the main contract and so the former was merely a minimum requirement.

More recently, we saw the above principles tested in the case of Lendlease Construction (Europe) Ltd v AECOM Limited [2023] EWHC 2620 (TCC). As we previously reported, we were delighted to act for AECOM in successfully defending a claim brought by Lendlease in relation to a settlement it had to make to the ultimate client in relation to a claim of defects in the plantroom of a newly constructed oncology centre at St James’s University Hospital, Leeds. Of the several issues which arose in the case, duty of care for design was amongst them.

AECOM’s appointment (as MEP / fire engineering services consultant) with Lendlease (the main design and build contractor) contained a strict obligation in relation to not putting Lendlease in breach of its contract with the ultimate client. However, the appointment also contained an overriding duty of care clause in relation to design liability.

In this case, Mr Justice Eyre in the TCC decided that the natural meaning of the latter clause (which was an overriding reasonable skill and care clause) was to impose a qualification on the strict duties which would otherwise have been owed by AECOM under the former ‘flow-down’ clause. Despite Lendlease’s arguments that the case should produce the same result as in Højgaard v E.ON (with the strict obligation prevailing), Mr Justice Eyre stated that none of the clauses in AECOM’s appointment could be seen as laying down competing requirements for specified performance criteria of the kind in Højgaard v E.ON, nor could they readily be seen as setting out inconsistent design obligations. The overriding nature of the clause was quite clear. However, this did not overrule Højgaard v E.ON, so contracts which are not so clearly drafted and/or include inconsistent design obligations (which is perhaps an increased risk in design and build contracts) may still give rise to design obligations more onerous than reasonable skill and care.

Conclusion

The need for an overarching appropriate design liability limitation and an FFP exclusion in respect of design and specification should therefore be strongly considered as part of the close review of design provisions in all appointments and contracts. Such clauses need to be carefully drafted to ensure that they ‘stand the test’ should a dispute arise, and the matter be determined by the Court.

In addition, it is important for project teams to obtain and review contract documents, particularly if the contract requires the Contractor to comply with those contract documents. Onerous obligations contained in those agreements increase the risk of parallel obligations arising.

Beale & Co can assist you to ensure that design obligations in contracts up and down your supply chain are appropriately worded to avoid the prospect of inconsistencies and/or uninsured losses in the event that things go wrong, or a claim is made. Please reach out to the authors of this article for further detail on how we can help.

[1] See table on page 6 of HKA’s Sixth Annual CRUX Insight Report ‘Forewarned is Forearmed’

Download PDF